Git Wizardry IV: Working directories and where to find them

In my previous post, I showed you how a Git repository records and organizes your changes.

The repository is a fantastic creature that should be handled with care. It’s similar to a database: it has a physical form in your file system, but you use a client to deal with the abstraction it represents. Modifying the repository directly is dangerous and can lead to corruption. Nevertheless, there are some things it’s useful to know.

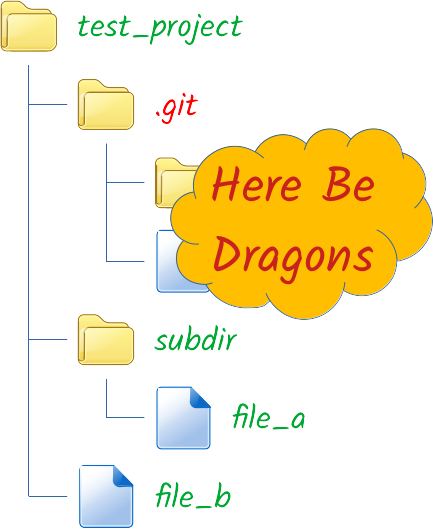

As simple as it sounds, a repository lives as a .git subdirectory in its working directory. Again, the layout of the files in this subdirectory is unimportant for developers using Git (well, except for those developing Git itself). You may see experienced wizards modifying some files within the repository, but it’s always safer to use your Git client.

It’s not uncommon to use the term ‘Git repository’ to refer to a working directory plus its .git subdirectory. Although it is not technically correct, it is widely accepted, since the context usually clarifies the intended meaning.

Where does a repository come from, in the first place? In other words, how can you get a Git repository to start working? You have two options:

-

If are starting a project from scratch, you need to init a repository. Just tell your client the path of your working directory, and it will create and populate the

.gitsubdirectory. Your working directory might contain some files, and Git will not modify or delete them, but it won’t record them either. You will have to add any code or resources to the repository at a later time. -

If you are jumping into an existing project, you need to clone a repository. You need to tell your client a URL to synchronize from, and where you want your working directory to be located. Git will create the working directory, then create and populate the

.gitsubdirectory, and finally populate the working directory with the files recorded at a certain commit.

If you were expecting some examples, with shell commands and their outputs, I’m sorry. Either option should be a piece of cake using a GUI client, even a basic one. So if you don’t have one yet, go get it!

Whether you init your repository or you clone it, this is a one-time process. The next time you want to interact with your repository, it will be right there waiting for you.

This one-to-one relationship between the Git repository and the working directory is something worth keeping in mind. For example, if you delete a working directory from your file system, you will delete the repository too. So not only you will loose all your local changes, but you will also loose all the committed work that has not been synchronized to a remote repository.

If you want to keep a working directory but remove the repository stuff, you can obviously go and delete the .git subdirectory. This may be useful if you want to pack your code but don’t want to disclose details about your development environment. Another case would be starting a new Git repository but obliterating the history of the old one. Or even migrating to another version control system (but who would want to do that?).

You can’t have two working directories recording changes to the same repository at the same time. I already explained that you can fight on several fronts using the same repository, by jumping from one branch to another, but not simultaneously. Using the same working directory for all your branches should not be a problem, since Git provides functionality to easily stash (i.e., save) your half-done work before checking out another branch.

If, despite all, you want two working directories of the same project in your file system, each one will have its own repository and will need to be synchronized independently. The simplest way to get a second working directory is making another clone from the remote repository. (You can even make a clone from the existing working directory, by giving a local URL to Git. But I do not recommend this option, since future changes in the second repository would be synchronized to the first one instead of the remote, and you probably don’t want that.)

I know I said you should not mess with things in the file system, but I will show you a safe, quick, alternate solution that may come in handy: just make a copy of the existing working directory. The resulting directory will contain a perfectly valid Git repository, completely independent from the source, but inheriting all its properties (including the remotes).

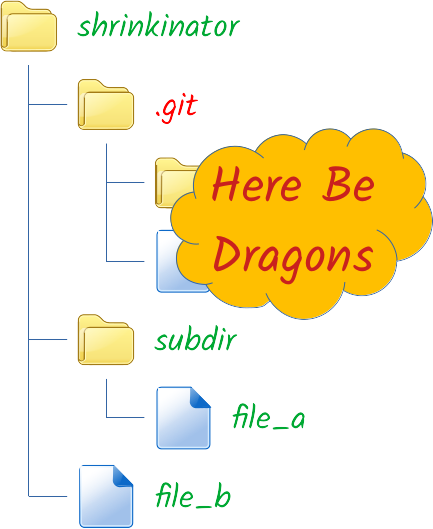

Talking about copies, you don’t need one if all you want to do is renaming your working directory. Just do it. The Git repository will still be valid after you change its parent directory from test_project to shrinkinator. Of course, you will have to tell your GUI client and your IDE the new path.

I mentioned in a previous post that some Git repositories don’t have a working directory. These are called bare repositories. In this case, instead of a .git subdirectory, the repository takes the form of a root directory with a .git extension (for example, shrinkinator.git).

Bare repositories are very useful for certain situations. Unfortunately, many GUI clients are not designed to work with them, so you have to use Git CLI in this case. But don’t worry, you have a lot of wizardry to learn before you will be in the need of dealing with a bare repository.

In my next post, I will explain how to use your working directory to record changes to the repository.

Git Wizardry

I: Spells don’t come easy

II: Choosing the right wand

III: The marauder’s graph

IV: Working directories and where to find them

V: The three realms